It’s pumpkin spice season. That means that not only can you get pumpkin spice lattes, but also pumpkin spice Oreos, pumpkin spice Cheerios, and even pumpkin spice oil changes.

The most important thing to know about “pumpkin spice” things is that they don’t actually taste like pumpkin. They taste like the spices that you use to flavor pumpkin pie. (Notable exception: Peter Suderman’s excellent pumpkin spice cocktail syrup, which does contain pumpkin puree.)

Last week economic historian Anton Howes posted a picture of the spice shelf at his grocery store and guessed that this would have been worth millions of dollars in 1600.

Some of the comments pushed back a little. OK, probably not millions but certainly a lot. Howes was alluding to the well-known fact that spices used to be expensive. Very expensive. Spices, along with precious metals, were one of the primary reasons for the global exploration, trade, and colonialism for centuries. Finding and controlling spices was a huge source of wealth.

But how much more expensive were spices in the past? One comment on Howes’ tweet points to an excellent essay by the late economic historian John Munro on the history of spices. And importantly, Munro gives us a nice comparison of the prices of spices in 15th century Europe, including a comparison to typical wages.

As I looked at the list of spices in Munro’s essay, I noticed: these are the pumpkin spices! Cloves, cinnamon, ginger, and mace (from the nutmeg seed, though not exactly the same as nutmeg). He’s even included sugar. That’s all we need to make a pumpkin spice syrup!

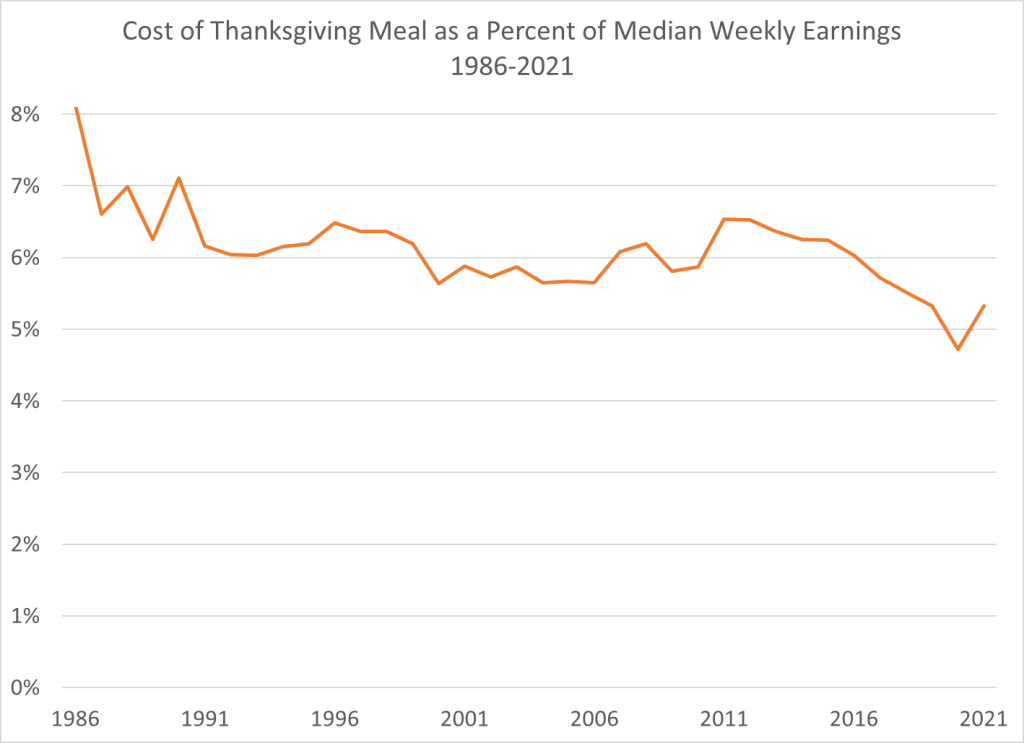

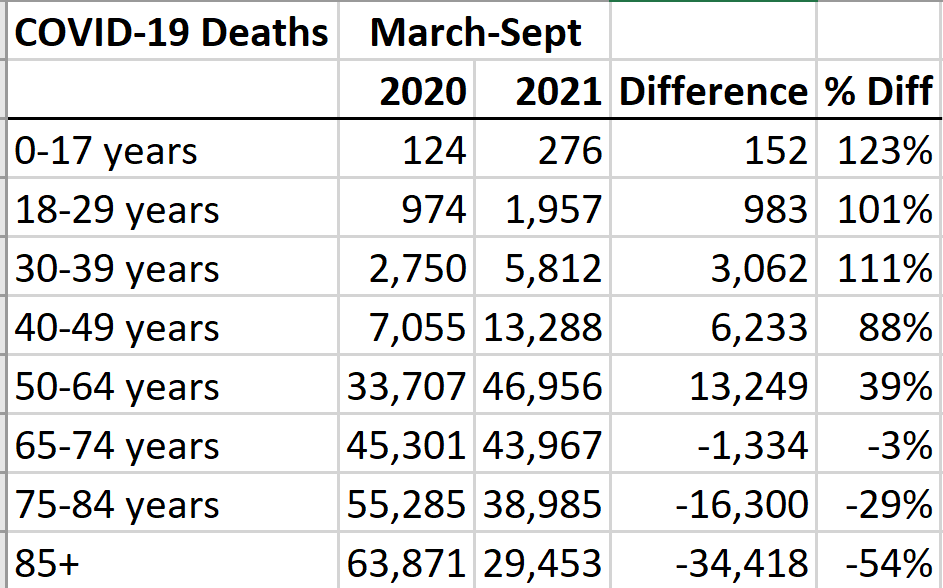

Last week in my Thanksgiving prices post I cautioned against looking at any one price or set of prices in isolation. You can’t tell a lot about standards of living by looking at just a few prices, you need to look at all prices. So let me just reiterate here that the following comparison is not a broad claim about living standards, just a fun exercise.

That being said, let’s see how much the prices of spices have fallen.

Continue reading